(Boylove Documentary Sourcebook) - Tashi: A Former Member of the "Gadrugba", the Dalai Lama's Ceremonial Dance Troupe, Recalls His Time as a Homosexual Passive Partner in Lhasa before the 1959 Tibetan Uprising

From The Struggle for Modern Tibet: The Autobiography of Tashi Tsering by Melvyn C. Goldstein, William R. Siebenschuh and Tashi Tsering (Abingdon, Oxon; New York: Routledge, 2015), first published in 1997 by M.E. Sharpe.

Note: Tsering was likely about fourteen and a half years old when he met the monk Wangdu.[1]

I had not been long in the city again when I was told to deliver something to an important monk official. There I met another monk named Wangdu, who worked as the major-domo of that official. He was extremely cordial, talking with me in a gentle and friendly manner, and I could tell he liked me. It was a pleasant change from the distance usually maintained between superiors and inferiors in Lhasa. I genuinely enjoyed meeting him, but soon forgot about it until, that is, a few days later when Pockmarks called me to his presence and announced:

“I have been asked to send you to Wangdula [la is a polite suffix added to names], the monk steward you met last week.”

That was all he said, but I knew immediately what was meant. Wangdu was asking for me to become his homosexual partner. In the manner customary to monks and monk officials in Lhasa, he had asked my superior for permission to invite me, and now I was being asked. For a moment I didn’t know how I wanted to respond, and I stood there speechless, trying quickly to think what to say. Pockmarks became impatient and again asked:

“What do you say? Will you do it?”

The question was firm and couldn’t be evaded, but I still didn’t know what I really wanted to say. After all the problems I had in Lhasa, I wasn’t sure if placing myself in a relationship with Wangdu would bring new difficulties or be the start of an era of success. I could have refused. I had no sexual feelings for him or for men in general. But I had liked him and also understood that having an intimate relationship with someone aligned with power and authority was an opportunity not to be lightly dismissed. So I decided to agree, and hesitantly said I would accept the invitation. It was the start of some of the best years of my life.

My decision and some of its ramifications have often seemed shocking or confusing—or both—when I have tried to explain them to foreign friends whose cultures and assumptions are so different from mine. But I didn’t find the invitation strange at all. To see it in proper perspective, you have to understand how the old Tibetan society was structured and what our customs were. For most of its history, Tibet has been a theocratic state. The bureaucracy that ran the government consisted of two kinds of officials—lay officials and monk officials. The original logic behind the creation of a class of monk officials was that as Tibet was a theocracy, monks should participate in administering the country. However, over the years, these monk officials became token monks in the sense that they neither lived in monasteries nor engaged in religious rites and prayer ceremonies. They were really bureaucrats who took religious vows. They wore a version of monks’ robes but worked as full-time government officials. Living in houses in the city like other officials, they wielded equal power and status with their lay aristocratic counterparts and were jointly in charge of government administration and its day-to-day operations. However, though they were “token” monks in most senses, they were required to obey the monks’ vow of celibacy.

In traditional Tibetan society, celibacy was defined specifically to mean abstaining from sexual acts with a female or, in a more general sense, from any sexual act that involved penetration of an orifice whether with a female or male. Consequently, anal sex with a male was as strictly prohibited as vaginal sex with a woman, and if discovered would mean expulsion from the monk rolls.

However, human nature being what it is, monks over the years developed a way to circumvent the iron law of celibacy. Monastic rules, it turned out, said nothing about other forms of sexual activity, and it became common for monks and monk officials to satisfy themselves sexually with men or boys by performing the sex act without penetrating an orifice. They used a version of the “missionary position” in which the monk official (the active, male-role player) moved his penis between the crossed thighs of a partner beneath him. Since no monastic disciplinary rule was technically violated, this behavior was condoned and rationalized as a pleasurable release of little significance.

The typical relationship was between monks—an adult monk (the male role) and a younger, boy monk—but there were several types of lay boys who were particularly desirable. One was the boys or young men who performed in the Tibetan opera, many of whom played women’s roles. Another was the young gadrugba dancers. Thus Wangdula’s request was not really unusual.

Obvious similarities aside, this “homosexuality” is quite different from homosexuality in Western terms. First, it was restricted almost exclusively to monks and monk officials and has always been looked on simply as a traditional way to get around a rule. The monks are not considered “gay” in the Western sense, because Tibetans don’t see this kind of behavior as the result of gender identity that is somehow biologically or culturally determined. Indeed, as a rule, in Tibet non-heterosexual activity by ordinary people is frowned on. Lay people seldom if ever have same-sex lovers. The monks’ behavior is just a fact of the way our culture has evolved. Thus, when the head of the gadrugba made his request, I was not shocked. It did not affect my sense of my own sexual identity, and I knew it would not affect anybody else’s opinion of me in that sense.

Agreeing to become Wangdula’s lover turned out to be a good decision for me. Though not a government official himself, as the steward of an important official Wangdu was well known in elite circles. I therefore benefited directly from his connections with status and power. Moreover, from the beginning of our relationship, he took an interest in me as an individual. He treated me kindly, frequently gave me presents when I went to his house, and, most important, was concerned about my career, playing a central role in my continuing education and my plans for advancement. Wangdu wrote in the beautiful Tibetan calligraphy of the Lhasa governmental elite, and he both valued education and understood my desire to learn. Sharing my own values and aspirations, he arranged for another official to accept me as a student, and later he put me in contact with two superb teachers who taught me different aspects of grammar and composition. Thus it turned out to be largely through Wangdula’s efforts and kindness that I finally got access to the tools I so desperately wanted and needed. But sometimes my life got a bit too exciting.

The Tibetan word for a boy in my situation is drombo. In our language the word literally means “guest,” but it also is a euphemism for “homosexual (passive) partner.” Because of Wangdu’s status and visibility, I became a very well-known drombo, and my reputation sometimes caused more trouble than I could handle. For example, once a powerful monk from the Sera Monastery became attracted to me and made several abortive attempts to abduct me for sexual pleasure. The monks of Sera included many famous dobdos, or “punk” monks. These were accepted deviant monks who carried weapons and swaggered through the streets, standing out in a crowd because of their openly aggressive manner and distinctive way of dressing. They were also notorious for fighting with each other to see who was toughest and for their sexual predation of lay boys. All schoolboys in Lhasa were fair game for these dobdos, and most tried to return from school in groups for protection against them.

I knew for some time that I was being pursued and had several close calls. But I was always able to escape until one fateful day when that monk caught me after a gadrugba performance in Lhasa and forcibly took me to his apartment in the monastery. He made me a prisoner, threatening me with beatings if I tried to escape or I refused to cooperate with him sexually. It was distasteful, but he released me after two days. The incident, however, reawakened my ambivalent feelings toward traditional Tibetan society. Once again its cruelty was thrust into my life. I wondered to myself how monasteries could allow such thugs to wear the holy robes of the Lord Buddha. When I talked to other monks and monk officials about the dobdos, they shrugged and said simply that that was just the way things were.

Wangdu was frustrated and angry with what happened, but knew he couldn’t say or do anything because the monk who kidnapped me was famous for his ferocity and brutality. Despite his position, Wangdula was afraid of becoming the target of retribution. The situation was made worse because this incident was not the only attempt of this sort. Other monks were attracted to me as well, and for a period of time I was in almost constant danger of being kidnapped. On several other occasions these attempts were successful. Each such episode infuriated Wangdula but also solidified the ties between us. He wasn’t simply angry at being bested. He genuinely cared about me and my welfare, and while I did not feel sexually attracted to him, I couldn’t help responding to his affection and concern. Moreover, I appreciated the good things he had done and was willing to do for me. And I liked him after a fashion. I think because of his sympathy for my desire to learn and because of the many stressful experiences we shared in those early years, a very strong bond developed between us that lasted until his death.

As I say, it has never been easy to talk about these things with people from cultures where the customs and assumptions about sexual matters differ greatly. To such people, for example, it would also be hard to explain the fact that during the years after I knew Wangdula, I had relationships with women. While Wangdula was jealous of other men, he had no objections to my relations with women. And there were times when Wangdula willingly shared me with other officials, and I accepted this arrangement because in spirit it was quite a different thing from the violent kidnappings. Moreover, it was simply what was done in those days.

Strange as this may seem to Americans, during this same period I also got married, at least briefly. My relationship with the woman I married began several years after my relationship with Wangdula started.

[...]

I was eighteen years old at the time but, as was the custom, was not consulted about the negotiations until the very end.

[...]

During this period, my relationship with Wangdula remained stable. He was always a good friend and a kind lover, and he continued to help me with my education and career. His sympathy, support, and approval were crucial, and gradually my spirits rose. I put the episode of my brief and unhappy marriage behind me, and I renewed my studies.

[...]

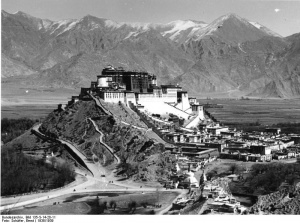

Life was very good for the next year or so, although sadly my relationship with Wangdu came to an end. The official whom Wangdu served got posted outside of Lhasa, and Wangdu had to accompany him. Our parting was difficult, but Wangdu again helped me, this time finding a new relationship for me with a very prominent monk official who lived in a big house right in front of the Potala Palace. My new host was rich and powerful, and I lived very comfortably with him. I had a small room of my own and joined the rest of the household for dinner in the evening when there was a joint meal.

But good things seldom last; and before long my life was to take twists and turns that I could never have imagined, even in my dreams.

References

- ↑ Melvyn C. Goldstein, William R. Siebenschuh and Tashi Tsering, The Struggle for Modern Tibet: The Autobiography of Tashi Tsering (Abingdon, Oxon; New York: Routledge, 2015), p. 20.