Ralph Nicholas Chubb : prophet and paiderast (Oliver Drummond)

Un article intitulé Ralph Nicholas Chubb: prophet and paiderast et signé Oliver Drummond fut publié en 1966 dans le premier numéro de la revue International Journal of Greek Love.

Une version française non illustrée, Ralph-Nicolas Chubb : prophète et pédéraste, avait déjà paru en mars 1963 dans la revue homophile Arcadie, sous la signature de Timothy d’Arch Smith.

Texte intégral

Si vous possédez des droits sur ce document

et si vous pensez qu’ils ne sont pas respectés,

veuillez le faire savoir à la direction de BoyWiki,

qui mettra fin dès que possible à tout abus avéré.

oliver drummond

London

ABSTRACT: Biographical sketch of Ralph Chubb, 1892-1960, British mystic and counterpart of Walt Whitman, but preoccupied with the love of boys (representing the Boy God or Divine Androgyne) rather than with Whitman’s “manly love of comrades.” During Chubb’s last thirty-odd years he wrote, designed and printed books promulgating his mystical philosophy, working in the tradition of William Blake. Examples of Chubb’s ideas and graphic work are included together with a bibliography of his published books.

The twentieth century is not one to cradle a prophet. The speed with which it moves, the fleshly things it covets and for which it works, the menace of annihilation with which it is constantly threatened—all deny a hearing to the idealist, the philosopher and the mystic. Great publishing houses pour forth more and more books of less and less literary importance, and the mystic remains unpublished and unheard.

But if the twentieth century ignores a prophet, it shuns a paiderast. We may have become more broad-minded, think little of the importance of marriage—little, even, of the once-whispered love of man for man—but we still treat the lover of boys with scandalized whispers, out-of-hand condemnation, and an unwillingness to comprehend what often is to the lover and beloved the most natural thing in the whole unnatural world. The adolescent boy, one of the most beautiful of God’s creatures, in whom love on all planes burns brightly in his young heart, must perforce be shunned as an object of love, and his lover must hang his head in shame and fear as the bright-eyed, long-legged creatures of his adoration flit across his day in street and park, and across his dreaming mind in the hours of night. Silent he must stand for fear that he may one day be harshly judged and hounded from his already lonely world.

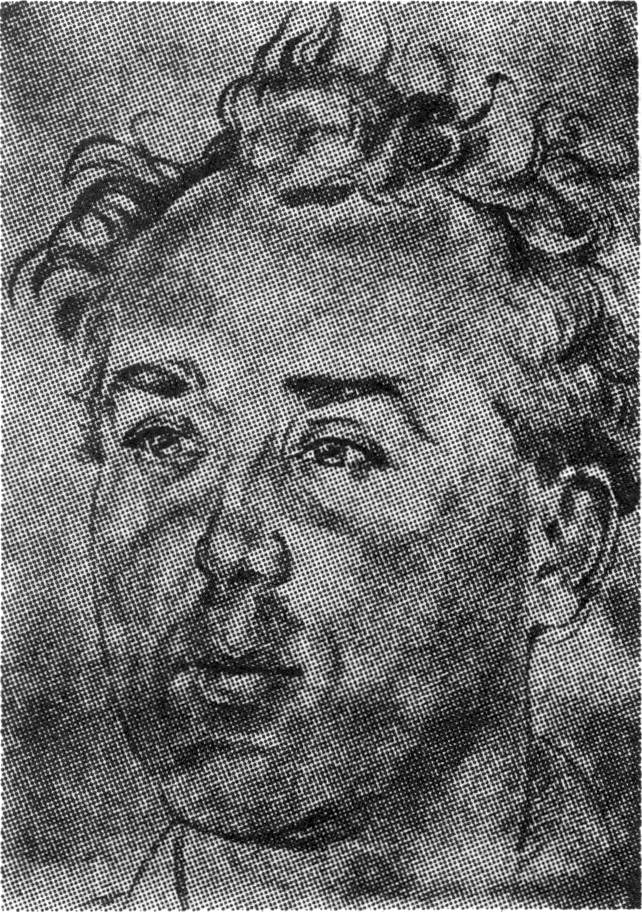

by Stanley Spencer.

Ralph Nicholas Chubb (1892-1960) was both a prophet and a paiderast. His insistence on a hearing and his intense belief in the truth of his writings forced him to devote almost his entire life not only to writing down his philosophies but to printing, publishing and distributing them himself. From 1924 until his death in 1960 he worked on his books alone and unaided, and never once faltered or tried to hide what he had to say. Fearlessly, one thinks perhaps recklessly, he distributed the handsome prospectuses of his volumes, each of which blared forth his philosophy, a philosophy he knew in his heart was condemned by the world he was trying to convert. Slowly and laboriously, when each page had reached the peak of technical perfection, the tall folios and the thick quartos would be published, each a clarion-call to the boy-lover. The world still knows little of Chubb and his work. The necessary limitation in size of his editions and the luxury of the great volumes keep his work known to but few. However, he had the good sense to deposit a copy of each of his books in the great libraries of England, where they will remain accessible for all time.

Ralph Chubb was born at Harpenden, Hertfordshire, in 1892. His family moved soon after his birth to St. Albans whence he won a scholarship to Selwyn College, Cambridge, in 1910. At the university he won a Blue for chess and thence he proceeded B.A. in 1913. A year later he enlisted in the army, and was mentioned in dispatches at Loos in 1915. He achieved the rank of captain but was invalided out in 1918. After the war, he studied for a time at the Slade School of Art and throughout the 1920’s he exhibited many oils and water-colors at the leading London galleries. In 1921 he left London, where he had lived while studying at the Slade, and moved with his family to Curridge, Berkshire. There he and his brother built from an old carpenter’s bench and some odd pieces of timber his first printing-press which was to print his first three books: Manhood (1924), The Sacrifice of Youth (1924) and A Fable of Love and War (1925). Only the last need concern us here. It is the tale in verse of a handsome warrior who, the night before a great battle is to be fought, meets a 16-year-old boy who is instantly smitten with admiration for the warrior. The latter tells the boy that tomorrow’s battle will be his last, whereupon the lad demands to be possessed by the soldier. He refuses, in spite of the boy’s argument that not all man’s seed is meant for woman. On the warrior’s departure a girl comes on the scene and seduces the boy, who is at first unwilling but eventually consents to sleep with her. The boy then goes off to the battle, and the girl stands listening to the sounds of war until she deems it safe to return home, hearing the sounds of victory from afar off. She discovers her house in ruins and spies an unrecognizably mangled corpse which, while she suspects it to be the boy’s, she prays is not so. She sees also the prone body of the warrior. She departs, and the warrior, regaining consciousness for a second, sees the corpse which is indeed the boy’s, and crawls over to die next to him. Mary, we are told, eventually despairs of the boy’s return, but is comforted by the birth of his child.

The poem cannot by any standards be called well-written, but it is important as the first glimpse we have of Chubb’s paiderastic writing and the last of his heterosexual interest. Woman, in the rest of Chubb’s work, exists only as mother of the man-child.

In 1927 Chubb abandoned his little hand-press and moved to a cottage just outside Aldermaston, where he was to remain the rest of his life. It is ironic to think of such a peace-lover living only a few miles from the huge atomic weapons research establishment, but this can only have been in Chubb’s very last years. Between 1927 and 1930 he published three further booklets, all printed for him by a commercial firm. The Book of God’s Madness (1928) is one of these, a long poem in blank verse. In it Chubb declares his love of boys:

- Delicious form of youth I love your view

Your feel, your sound, your scent, your taste, your all—

. . .

I speak to women. — Here behold your king!

. . .

The love of man and youth is as two fires

Of mother and son two strong and gentle streams.

The love of man and maid a sluggish rill.

The book contains a charming full-page woodcut of two naked boys on the seashore.

Songs of Mankind (1930), a far more powerful collection of poems illustrated with woodcuts, some erotic, continues to expound Chubb’s philosophy. In a wild, prophetic poem ‘Song of My Soul’ he howls his evocation to the boys of today:

- O burning tongue and hot lips of me explore my love!

Lave his throat with the bubbling fountain of my verse!

Drench him! Slake his loins with it, most eloquent!

Leave no part, no crevice unexplored; delve deep, my minstrel tongue!

He is charged, he proclaims, to state that all boys are lovers of men.

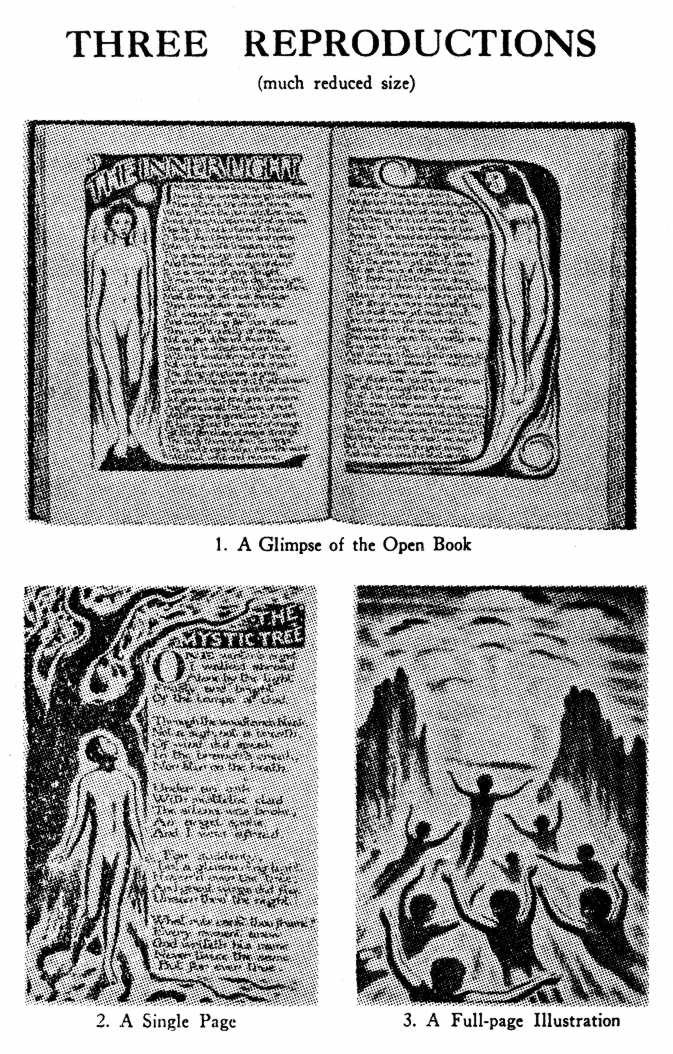

For a long time Chubb had been contemplating the production of a perfect book. ‘I always visualized,’ he said, ‘a method which would combine poetical idea, script and design, in free and harmonious rhythm—all unified together—so as to be mutually dependent and significant.’ In 1929 he produced a short work, An Appendix, on a duplicating machine which may have given him the idea of lithographic work. In June 1931 his dream was realized and his first lithographic book, The Sun Spirit, was published. Like the three that succeed it, it is a tall folio volume, measuring 15¼” × 11”. No metal types are used, and the whole is a lithographic reproduction of Chubb’s own script and illustrations. It is not really possible to give an idea of the intense complexity of the eight books which Chubb produced in this medium. In some cases it took him five or six years to complete one volume. He would pull masses of proofs until the inking and the pressure were exactly as he wanted, noting in pencil on these trial sheets faults to be corrected in the next pull. He used only the finest handmade paper for the books which the expense of production forced him to produce only in a very limited number. Even further to enhance the technical perfection, in a tiny number of copies of each book, he would illuminate certain pages in water-color. The British Museum copy of Water-Cherubs (1937) has every leaf hand-colored and the pages flash with the bright tints.

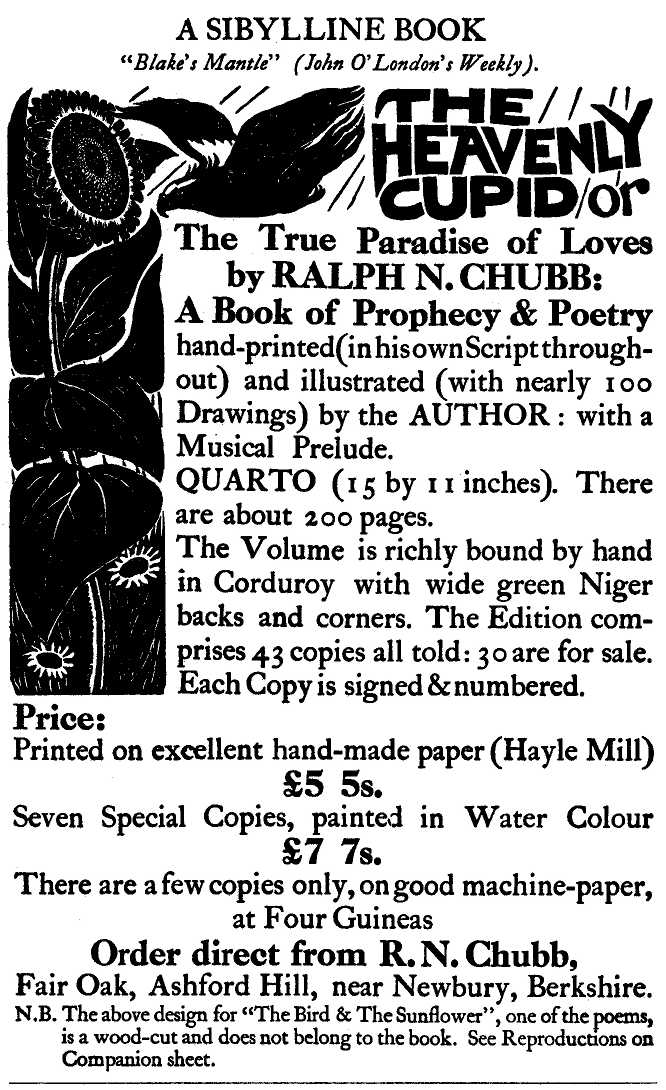

The eight lithographic books fall neatly into three groups. The first is a group of four: The Sun Spirit (1931), The Heavenly Cupid (1934), Water-Cherubs (1937), and The Secret Country (1939).

The Sun Spirit is a visionary drama of which the plot is briefly this: an ancient Sage puts his youthful disciple through a series of psychic ordeals, each more terrible than the last, until at length Lucifer himself appears. He is routed by a young seer, who—like the Apostle John—has seen a Vision of Light. This divine vision is manifested from the beginning as a beautiful Boyish Figure, identifiable as the Boy Jesus or as the Grecian Eros: the divine consummated humanity embracing both male and female elements in spiritual perfection, ‘the Divine Androgyne.’ The book is dedicated ‘to you true visionary lovers of the Boyhood Divine.’ It contains an extremely interesting and important account of the author’s boyhood. We read of his early sexual longings and of his passionate friendship at 18 with a boy three years his younger.

The Heavenly Cupid is a uniform folio about four times the length of the preceding book. It was naturally compared with the Prophetic Books of William Blake, but, as the reviewer in the Times Literary Supplement of December 4, 1934, said: ‘No one could suspect this book of being a mere literary imitation; it is obviously an instance of the parallel working of a similar mind.’ The bulk of the work is a long prophetic essay on the arrival on earth of a third sex or ‘Third Dispensation.’ In it is a passage throwing some light on Chubb’s reconciliation of spiritual and physical love of boys. Then follows a long poem with decorative borders of boys and youths, entitled ‘Midway through Life,’ in which Chubb evokes the memory of boys long dead and gone, slaughtered by war or repressed by society’s narrow-mindedness. It is reminiscent of much of Whitman, especially of the verse in Drum-Taps, ‘Vigil strange I kept on the field one night.’ Further poems and short discourses complete the book, including one extremely erotic poem ‘Boys on the Quay.’

Water-Cherubs is a poem in rhyming couplets about boys bathing, with an introduction and postscript on boy-love and a little erotic prose fable, ‘Alfie’s Tale.’ Especially noteworthy in the book is a full-page plate of two boys, head and shoulders, very much in the manner of Picasso and quite unlike Chubb’s usual work.

The Secret Country, the final volume of the first group, limited drastically to 37 copies and published just after the outbreak of World War II, consists of a collection of allegorical fables rather in the style of the medieval romances of knights in armor and handsome yellow-haired princes, and of descriptions of Chubb’s visionary experiences.

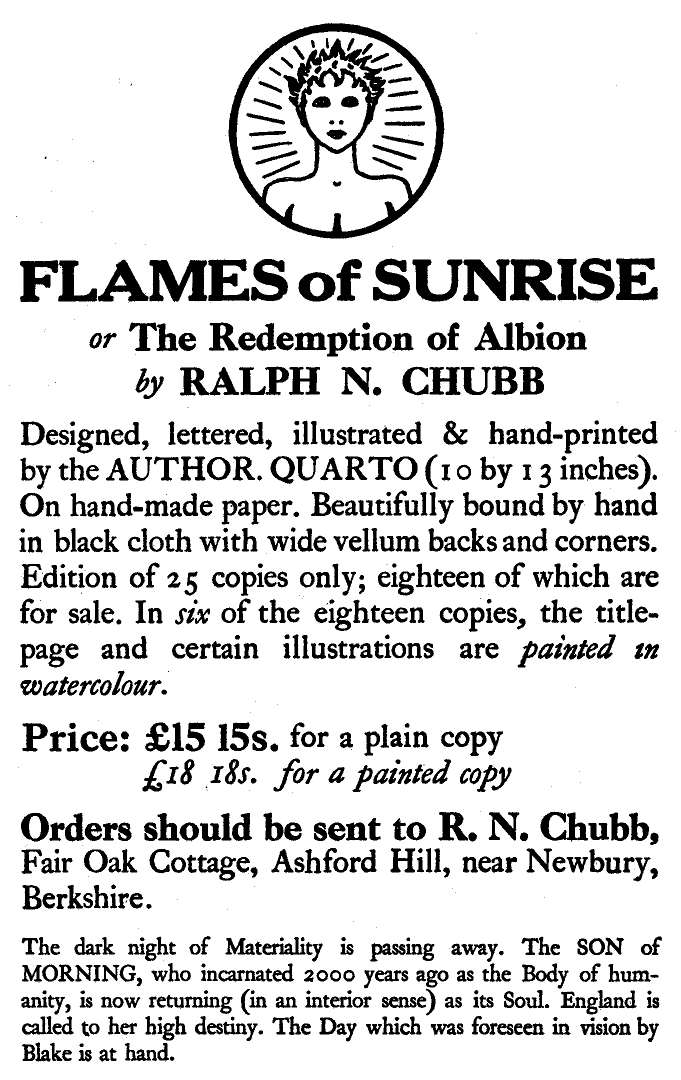

The second group of lithographed volumes consists of two titles: The Child of Dawn (1948) and Flames of Sunrise (1954). These are far less easy to analyze and discuss; the symbolisms are thickly scattered and the chapters subdivided time and again to express and re-express in various ways the same philosophy.

World War II had clearly influenced Chubb in his retirement as greatly as had the first war, though in a different manner. The boys in the illustrations of this second group differ from those of the first. Formerly slim, dark, cat-eyed and seductive, now they become blond, hard, masculine, often akin to the better drawings of male-model magazines though far more youthful.

And Chubb here considered himself the herald of the Third Dispensation, sent by God to proclaim the coming of the androgynous Man-Child who would govern the world. Let us hear his own words:

- Raf, who is the angel Rafi grown to maturity, is the herald angel of the Third Dispensation, the angel of dawn; and it is through Anglia, his mother country, that he shall redeem the earth. For she is that Lapis Angularis, the headstone in the corner, that in the last age shall crown the universal pyramid of world-evolution. Anglia is the land of the rose and the crown. And her golden-hair’d rose-lipped blue-eyed striplings shall be call’d no longer Angles but Angels. And generation shall cease; for the golden crown of the universe shall be set upon the head, and the golden sceptre in the hand, of the eternal Manchild.

The third group of lithograph books comprises two titles: Treasure Trove (1958) and The Golden City (1961, posthumous). These are quartos, bound in green cloth, and reflect the tranquillity of Chubb’s mind at the end of his life. They contain few prophecies and consist mostly of pastoral tales written by Chubb when he was a child. Boy-love is hardly mentioned. Had Chubb lived, he would not (so he told his sister) have published any further books. His work was finished; and it was for mankind to read and understand.

It can be easily said that the work of Ralph Chubb is the product of a sick and perverted mind, but a more peaceful, kind and gentle man could not be imagined by the small circle of his friends who still remember him and to whom I have spoken about him. In the silence of Chubb’s studio, the boy was his constant vision and delight. Perhaps the drive behind his mind was a desire to recapture his own lost boyhood and to relive his idyllic days with his 15-year-old lover. Often, in his visions, Chubb tells us that he magically regained his boyhood, or was transformed into an adolescent by a boy’s touch and accepted into the naked groups he was watching. He predicts that the time will come when all mankind will have the form of a boy who never grows old. The key to the alchemy of rejuvenation has yet, alas, to be found.

1. MANHOOD: A POEM. Curridge 1924. 8vo. 200 copies. Printed by Chubb in metal types.

2. THE SACRIFICE OF YOUTH: A POEM. Curridge 1924. 8vo. 45 copies. Printed by Chubb in metal types.

3. A FABLE OF LOVE AND WAR: A ROMANTIC POEM. Curridge 1925. 8vo. 200 copies. Printed by Chubb in metal types.

4. THE CLOUD AND THE VOICE (A FRAGMENT). Newbury 1927. 8vo. 100 copies. Printed commercially for Chubb.

5. WOODCUTS. London, Andrew Block, 1928. 4to. 235 copies. Chubb’s only commercially published book.

6. THE BOOK OF GOD’S MADNESS. [Newbury 1929.] 100 copies. Printed commercially for Chubb.

7. AN APPENDIX. Newbury 1929. 4to. 50 copies. Mimeographed by Chubb. Not for sale.

8. SONGS OF MANKIND. Newbury 1930. 4to. 100 copies. Printed commercially for Chubb.

9. THE SUN SPIRIT: A VISIONARY PHANTASY. [Newbury 1931.] Folio. 30 copies. Lithographed by Chubb.

10. THE HEAVENLY CUPID: OR, THE TRUE PARADISE OF LOVES. [Newbury 1934.] Folio. 43 copies. Lithographed by Chubb.

11. SONGS PASTORAL AND PARADISAL. Brockweir: the Tintern Press, 1935. The first book printed on a private press owned by Vincent Stuart.

12. WATER-CHERUBS: A BOOK OF ORIGINAL DRAWINGS AND POETRY. [Newbury 1937.] Folio. 30 copies. Lithographed by Chubb.

13. THE SECRET COUNTRY: OR, TALES OF VISION. [Newbury 1939.] Folio. 37 copies. Lithographed by Chubb.

14. THE CHILD OF DAWN: OR, THE BOOK OF THE MANCHILD. Newbury [1948]. 4to. 30 copies. Lithographed by Chubb.

15. FLAMES OF SUNRISE: A BOOK OF THE MANCHILD CONCERNING THE REDEMPTION OF ALBION. Newbury [1954]. 4to. 25 copies. Lithographed by Chubb.

16. TREASURE TROVE: EARLY TALES AND ROMANCES WITH POEMS. Newbury [1957]. 4to. 21 copies. Lithographed by Chubb.

17. THE GOLDEN CITY WITH IDYLLS AND ALLEGORIES. Newbury [1961]. 4to. 18 copies. Lithographed by Chubb and posthumously published by his sister, Miss Muriel L. Chubb.

[For a somewhat different interpretation of Chubb’s work, see Greek Love, chapter XV ad fin. It seems to me that the parallel with Walt Whitman deserves more emphasis than it has received either there or here. Whitman until 1853 was a journalist of no great merit; and in 1853 he had a mystical experience of the kind analyzed by Richard Maurice Bucke in Cosmic Consciousness. Afterwards his writings took a markedly mystical and prophetic turn, and he preached what amounted to a religion of universal love centering around a masculine (though often androgynous) ideal of mankind. Chubb until 1927 or 1928 produced nothing of any great consequence; but suddenly he too seems to have taken an enormous leap and thereafter his works are mystical and prophetic, not imitating Blake or Whitman, but in their own original language proclaiming much the same kind of religious insight, centering around the archetypal androgynous Child God. To quote The Heavenly Cupid: “I prophesy the melting-away of the male and female shades, and the visible emergence of the spiritual boyhood, ambisexual unisexual.” Compare the esoteric meaning of Galatians 3:28: “There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is neither male nor female (sc. in the kingdom of God, the new dispensation), for you are all one in Christ Jesus.” (R.S.V.) The same theme occurs again and again in the recently-translated Gospel of Thomas, a collection of sayings ascribed to Jesus and of apparently earlier date than the canonical gospels. It also recurs in Indian and Far Eastern mystical writings both ancient and recent. Its appearance in Chubb’s work may again be ascribed to parallel working of a similar mind—a mind kindled in 1928 or 1929 by some kind of mystical experience amounting to “cosmic consciousness” and thereafter using the Boy God as a prime symbol much as Whitman used the manly love of comrades. J.Z.E.]

| Version française de 1963 : Ralph-Nicolas Chubb : prophète et pédéraste |

Voir aussi

Source

« Ralph Nicholas Chubb : prophet and paiderast » / Oliver Drummond, in International Journal of Greek Love, Vol. 1, No. 1, p. 5-17. – New York : Oliver Layton Press, [1966]. – 72 p. : ill. ; 23 × 16 cm.