Pederastic couples in Japan: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

== Heian period == | == Heian period == | ||

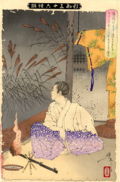

[[ | [[Image:120px-Yoshitoshi Ariwara Narihira.jpg|thumb|Ariwara no Narihira]] | ||

* Shinga and [[Ariwara no Narihira]] | * Shinga and [[Ariwara no Narihira]] | ||

** The relationship was between a bishop and a young aristocrat. Narihira, famous for his beauty, was a grandson of [[Emperor Heizei]], while Bishop Shinga<font face="SimSun">(</font>801 <font face="SimSun">- </font>879) was a younger brother and disciple of [[Kūkai]]. | ** The relationship was between a bishop and a young aristocrat. Narihira, famous for his beauty, was a grandson of [[Emperor Heizei]], while Bishop Shinga<font face="SimSun">(</font>801 <font face="SimSun">- </font>879) was a younger brother and disciple of [[Kūkai]]. | ||

Revision as of 13:01, 30 June 2015

Note this page is still under construction. |

The tradition of Japanese pederasty originated in the relationships between Buddhist and Shinto clerics and their acolytes, who were known as chigo(稚児 ) .

It was adopted in medieval times by the samurai warrior class, which utilized it as a means of acculturating young samurai into the warrior community, and as a means of reinforcing loyalty and friendship between comrades. It was known as Shudō and constructed as a Way, or dō that that had an ethic and an aesthetic, that could be transmitted, and was authoritative.

After the pacification of the country under the Tokugawa shogunate the tradition was borrowed by the rising townsmen classes and became increasingly commercialized.

A famous Pederastic couples is enumerated as follows.

Asuka period

Unknown.[1]

Nara period

- Ōtomo no Yakamochi and Fujiwara no Kusumaro

- The youth was the son of Fujiwara no Nakamaro a.k.a.Emi no Oshikatsu.

- Ōtomo no Yakamochi and Kon no Myogun or Yo no Myogun

- Their mutual love poems appear in the oldest existing collection of Japanese poetry, "Man'yōshū".

- Kūkai (Kōbō-Daishi) and Taihan

- Kukai was the legendary founder of the Japanese male love tradition, placing this relationship around 788.

- Saichō (Dengyō Daishi) and Taihan

- Although Taihan was Saicho's favorite pupil and promised to be the successor of archibishop in Tendai Buddhism, also around 788, he went to study Shingon Buddhism under Kukai. No matter how insistently Saicho asked Taihan to come back, his entreaties were useless (several letters are extant). Wholly devoted to Kukai, Taihan became one of the Ten Disciples of Kukai and never went back to Saicho. Indignant, Saicho severed his connection with Kukai, after which these two greatest founders of Japanese Buddhism sects remained at odds.

Heian period

- Shinga and Ariwara no Narihira

- The relationship was between a bishop and a young aristocrat. Narihira, famous for his beauty, was a grandson of Emperor Heizei, while Bishop Shinga(801 - 879) was a younger brother and disciple of Kūkai.

- Fujiwara no Yorimichi and Minamoto no Nagasue

- Sensai-Shonin and Umewaka

- Emperor Shirakawa and Fujiwara no Akitaka

- Emperor Shirakawa loved many handsome boys, especially Fujiwara no Akitaka who was called to the Emperor's presence every night, and all of whose requests were granted; Akitaka was nicknamed "Regent of the Night".

- Emperor Shirakawa and Fujiwara no Munemichi(Akomaru)

- Emperor Shirakawa and Fujiwara no Nobumichi

- Nobumichi was the son of Fujiwara no Munemichi, a former wakashu of the emperor.

- Emperor Shirakawa and Fujiwara no Narimichi

- Narimichi was another son of Fujiwara no Munemichi.

- Emperor Shirakawa and Fujiwara no Akisue

- Emperor Shirakawa and Fujiwara no Nagazane

- Nagazane was a son of Fujiwara no Akisue, the emperor's former wakashu.

- Emperor Shirakawa and Minamoto no Toshiaki

- Emperor Shirakawa and Taira no Masamori

- Masamori would be, in due course, the grandfather of Taira no Kiyomori.

- Emperor Shirakawa and Taira no Tametoshi

- Emperor Shirakawa and Fujiwara no Morishige

- Emperor Shirakawa and Tachibana no Yorisato (Imainumaru)

- Emperor Shirakawa and Jiromaru

- Minamoto no Arihito and Ajimaru

- Arihito was the nephew of Emperor Shirakawa.

- Emperor Toba and Fujiwara no Ienari

- Emperor Toba loved many beautiful youths, from aristocrats to common dancers, most of all Fujiwara no Ienari, who monopolized the political power. The confrontation between Ienari and Fujiwara no Yorinaga was one of the causes of The Hōgen Rebellion.[3]

- Emperor Toba and Fujiwara no Nobumichi

- Nobumichi had also been the beloved of Emperor Shirakawa.

- Emperor Toba and Fujiwara no Narichika

- The youth was the son of Fujiwara no Ienari, a former wakashu of the emperor.

- Emperor Toba and Hata no Kimiharu

- Emperor Toba and Koma no Norusuke

- Emperor Toba and Saigyō Hōshi

- Emperor Go-Shirakawa and Fujiwara no Nobuyori

- Emperor Go-Shirakawa had many love relationships with handsome youths, including several nobles and some samurai. The Emperor dearly loved Nobuyori. His boundless love toward his favorite boy was one of the major causes of the Heiji Rebellion.

- Emperor Go-Shirakawa and Fujiwara no Narichika

- Emperor Go-Shirakawa and Taira no Sukemori

- Emperor Go-Shirakawa and Fujiwara no Motomichi (Konoe Motomichi)

- Emperor Go-Shirakawa and Taira no Narifusa

- Emperor Go-Shirakawa and Fujiwara no Mitsuyoshi

- Fujiwara no Yorinaga and Fujiwara no Tadamasa

- Fujiwara no Yorinaga was a famous male-lover. In his diary there are many mentions on his erotic life with many men and boys. Fujiwara no Tadamasa (1129 - 1193), a young nobleman, was not only one of Yorinaga's lovers, but also Yorinaga's father Fujiwara no Tadazane's lover.[4]

- Fujiwara no Yorinaga and Fujiwara no Tamemichi

- Fujiwara no Yorinaga and Fujiwara no Kin'yoshi

- Fujiwara no Yorinaga and Fujiwara no Ieaki

- Fujiwara no Yorinaga and Fujiwara no Narichika

- Fujiwara no Yorinaga and Fujiwara no Takasue

- Fujiwara no Yorinaga and Minamoto no Narimasa

- Fujiwara no Yorinaga and Minamoto no Yoshikata

- Fujiwara no Yorinaga and Saeki no Sadatoshi

- Fujiwara no Yorinaga and Hata no Kanetoo

- Fujiwara no Yorinaga and Hata no Kimiharu

- Fujiwara no Yorinaga and Kimikata

- Kimikata had been a male-dancer in the Shitennō-ji Temple.

- Taira no Kiyomori and Matsuoo

- Kumagai Naozane and Taira no Atsumori

- Mongaku (high priest) and Taira no Takakiyo(Rokudai)

- Shunkan and Arioo

- Saito Musashibō Benkei and Minamoto no Yoshitsune

- Minamoto no Yoshinaka and Imai Kanehira(1152-1184)

- Yoshinaka adored Imai so much that he wanted to die with him since they were children according to the Heike Monogatari and Zeami Motokiyo's nohplay "Kanehira". In the end they both died together in Awazu.

Kamakura period

- Emperor Go-Toba and Fujiwara no Hideyoshi (1184-1240, 藤原秀能)

- Emperor Go-Toba and Minamoto no Michiteru (1187-1243)

- Minamoto no Yoriie and Nakano Yoshinari

- Minamoto no Sanetomo and Wada Tomomori[[[5]]]

- Unkei and Hōjumaru

- Hōjō Yoshitoki and Fukami Saburoo

- Yoshitoki was killed by Saburoo out of nanshoku jealousy .

- Hōjō Takatoki and Sasaki Takauji

- Yoshida Kenkō and Myōmatsumaru[[[6]]]

- Emperor Go-Daigo and Fujiwara Tametsuna

- Emperor Go-Daigo and Hino Kumawakamaru (Hino Kunimitsu)[[[7]]]

- Emperor Go-Komatsu and Umewaka

- Ikkyū and Shōben

- Ikkyū was the son of Emperor Go-Komatsu.

- Jikyū( priest of Kenchō-ji) and Shiragiku (or Shiragikumaru, beautiful chigo)

Muromachi period

- Ashikaga Takauji and Aeba Myōzurumaru (Aeba Ujinao)

- Ashikaga Yoshimitsu and Zeami Motokiyo

- Nijō Yoshimoto and Zeami Motokiyo

- Ashikaga Yoshimitsu and Ogamaru (boy-dancer)

- Ashikaga Yoshimitsu and Dōami

- Ashikaga Yoshimitsu and Rokkaku Mitsutaka or Kamejumaru (1365-1416)

- Ashikaga Yoshimochi and Akamatsu Mochisada (?-1427)

- Shogun Yoshimochi, son of Yoshimitsu, granted lands which his beloved mismanaged. His own family denounced him, and he had to commit seppuku by order of his lover, the shogun.

- Ashikaga Yoshimochi and Zōami

- Ashikaga Yoshinori and Akamatsu Sadamura (nephew of Akamatsu Mochisada)

- For love of Sadamura, Shogun Yoshinori lost his life in 1441, assassinated by Akamatsu Mitsusuke, whose lands he had wanted to take and give to Sadamura.

- Ashikaga Yoshinori and Otoami ( adopted son of Zeami Motokiyo ).

- Ashikaga Yoshimasa and Akamatsu Norinao

- Norinao, granted lands at the time in possession of Yamana Sozen, was attacked by the latter and took his own life. The conflict ballooned into the Ōnin civil war of 1467.

- Ashikaga Yoshihisa and Yūki Hisataka

- Ashikaga Yoshihisa and Hirosawa Hisamasa or Kanze Hikojiro

- Hosokawa Katsumoto and Naitō Shirōzaemon

- Hosokawa Katsumoto and Akamatsu Masanori

- Katsumoto's excessive love for the youth was one of the major causes of Ōnin War.[[[8]]]

- Hosokawa Katsumoto and Yokogoshi Matasaburō

- Hosokawa Masamoto and Hosokawa Sumiyuki (1489-1507, son of Kujō Masamoto)

- Hosokawa Takakuni and Yanagimoto Kenji

- Takakuni, despite having sworn eternal love to Kenji, allowed Kenji's brother to be murdered. Later Kenji rose in vengeance against him with an army.

- Yanagimoto Kenji and Takahata Jinkurō

- Knowing Kenji prepared a rebellion, Jinkuro vowed silence, but refused to break his allegiance to Lord Takakuni, warning Kenji that despite their love, he would not hesitate to kill him in battle.

Sengoku period

- Hōjō Ujiyasu and Hōjō Tsunashige

- Hōjō Tsunashige was loved by Hōjō Ujiyasu.[[[9]]]

- Ōuchi Yoshioki (father of Ōuchi Yoshitaka) and Sue Yoshikiyo (elder brother of Sue Harukata) and Sue Harukata.

- Ōuchi Yoshitaka and Sue Harukata[[[10]]]

- Ōuchi Yoshitaka and two sons of Mōri Motonari ; Mōri Takamoto and Kobayakawa Takakage.

- Ōuchi Yoshitaka and Sagara Taketo

- Saitō Dōsan and Toki Tarohoshimaru (son of Toki Yorinari )

- Takeda Shingen and Kosaka Masanobu

- In 1543 the 22-year-old future Daimyo sealed a written vow of love (still in existence) with his 16-year-old retainer, who served him as samurai in battle and page in peacetime.[[[11]]]

- Takeda Shingen and Uesugi Kagetora (or Hōjō Ujihide; son of Hōjō Ujiyasu ).

- Uesugi Kagetora was reputed to be the most handsome boy in Kantō region, so he was loved by both Takeda Shingen and Uesugi Kenshin.

- Uesugi Kenshin and Kawada Nagachika (1545?-1581)

- Uesugi Kenshin and his two adopted sons; Uesugi Kagekatsu (Kenshin's nephew) and Uesugi Kagetora (son of Hōjō Ujiyasu).

- Uesugi Kenshin and Iwai Tanbanokami

- Uesugi Kagekatsu and Naoe Kanetsugu.[[[13]]]

- Uesugi Kagekatsu and Kiyono Naganori (1573?-1634)

- Satake Yoshishige(1547-1612) and Ashina Moritaka

- Uragami Munekage and Ukita Naoie

- Miyoshi Nagayoshi and Matsunaga Hisahide

- Matsunaga Hisahide and Yagyū Shigeyoshi (younger brother of Yagyū Muneyoshi)

- Amago Haruhisa and Ushio buzen'nokami

- Amago Katsuhisa and Yamanaka Shikanosuke

- Ashikaga Yoshiteru and Matsui Sadonokami

- Sadonokami remained as the Shogun's lover until he reached adulthood, when he entered the service of the Hosokawa family, where his descendants can be found to the present day.

- Ashikaga Yoshiteru and Oodate Iwachiyomaru

- The Jesuit Father Luis Frois writes of the 13-year-old (15-year-old in Japanese document) page's seppuku upon the death of his lord, the Shogun in 1565.

- Ashikaga Yoshiteru and Minoya Koshiro ( the 16-year-old page )

- Imagawa Ujizane and Miura Yoshishige.

- Imagawa Ujizane and two sons of Ukai Nagateru (Imagawa Ujzane's cousin); Ukai Ujinaga and Ukai Ujitsugu.

- Oyamada Masayuki and Nishina Morinobu (son of Takeda Shingen).

- Ashikaga Yoshiaki and Ueno Masanobu(Hori Magohachirō)

Azuchi-Momoyama period

- Oda Nobunaga and Hori Hidemasa

- Oda Nobunaga and Manmi Senchiyo (Manmi Shigemoto) (1549-1578)

- Manmi Senchiyo is famous as one of the four most beautiful boys (bishōnen) in the Sengoku period.[[[14]]]

- Araki Murashige(1535-1586) and Manmi Senchiyo (Manmi Shigemoto)

- Manmi Senchiyo was formerly a page to Araki Murashige. But he was so beautiful that Oda Nobunaga took him away from Araki.

- Oda Nobunaga and Hasegawa Hidekazu (? -1594)

- Oda Nobunaga and Maeda Inuchiyo (Maeda Toshiie )

- Maeda Toshiie was very attractive as a boy, so at the age of 15 he became Oda Nobunaga's favorite and was always with him day and night. Afterwards at a celebration banquet in 1576, Oda Nobunaga related his reminiscences and told him "You were my very favorite boy indeed, and every night slept with me on the same bed(futon)" holding Toshiie's beard with smile. Listening to his memoirs, all samurai warriors and daimyo at the banquet were envious of Toshiie's good luck, and remarked with one voice "Bravo Maeda Toshiie! You exremely lucky man, because you were profoundly loved by our lord prince Nobunaga".[[[15]]]

- Oda Nobunaga and Mori Ranmaru (1565-1582)

- Nobunaga met his end in an ambush in 1582, at Honnō-ji temple, assassinated by Akechi Mitsuhide, whose lands he had wanted to take and give to Mori Ranmaru. Ranmaru, still in his teens, died fighting by Oda's side.

- Oda Nobuyuki (1536 - 1557, younger brother of Oda Nobunaga) and Tsuzuki Kurando (Jujo)

- Oda Nobutoki (?-1556, younger brother of Oda Nobunaga) and Sakai Magoheiji

- Nobunaga's brothers ruined themselves because of excessive love for their favorites.

- Akechi Mitsuhide and Akechi Samanosuke(Akechi Hidemitsu)

- Kaiho Yusho(Kaihō Yūshō) and Saitō Toshimitsu

- Otani Yoshitsugu and Ishida Mitsunari

- Toyotomi Hidetsugu and Fuwa Bansaku(or Fuwa Mansaku,1578-1595)

- Hidetsugu, regent to the emperor, ended up having to commit seppuku in 1595, joined by his beloved Fuwa Bansaku.

- Fuwa Bansaku is famous as one of the three most beautiful boys (三大美少年bishōnen) in the Sengoku period.[[[16]]]

- Toyotomi Hidetsugu and Yamada Sanjūrō

- Toyotomi Hidetsugu and Yamamoto Tonomo-no-suke

- Gamō Ujisato and Nagoya Sanzaburō (1572 - 1603)

- Nagoya Sanzaburō is famous as one of the three most beautiful boys (三大美少年bishōnen) in the Sengoku period.[[[17]]]

- Kimura Yoshikiyo and Asaka Shōjirō

- Asaka Shōjirō is famous as one of the three most beautiful boys (三大美少年bishōnen) in the Sengoku period.[[[18]]]

- Katō Mitsuyasu and Akiyama Tamon

- Katō Kiyomasa and Kōzuki Sazen

- Fukushima Masanori and Kashiwagi Unume

- Fukushima Masanori and Katayama Uzen

- Date Masamune and Katakura Kojūrō Shigetsuna(later Katakura Shigenaga

- Kobayakawa Hideaki and Katakura Kojūrō Shigetsuna(later Katakura Shigenaga

- When Katakura came up to Kyoto, Kobayakawa Hideaki fell in love with him at first sight and wooed him, pursuing him with intense passion.[[[19]]]

- Mori Katsunaga(Mōri Katsunaga)(1577-1615)and Yamauchi Tadayoshi (1592-1665, nephew and adopted son of Yamauchi Kazutoyo)

- Sagawada Masatoshi and Ishikawa Jōzan( or Ishikawa Shigeyuki, 1583-1672)

- Sakazaki Naomori and Indō Shizuma

- Ukita Samon( nephew of Sakazaki Naomori) and Indō Shizuma

- Niwa Nagashige and Tokugawa Hidetada

- Yoshida Kiyoie(-1599) and Hirata Munetsugu(-1599)

- Nakamura Kazutada(1590-1609) and Hattori Kunitomo

- Nakamura Kazutada(daimyō of Yonago) and Tarui Nobumasa

Tokugawa period (Edo period)

- Tokugawa Ieyasu and Ii Manchiyo (Ii Naomasa)

- One of many beloveds of the shogun, Manchiyo was a scion of an allied powerful clan.[[[20]]]

- Tokugawa Ieyasu and Mizuno Tadamoto (1576-1620)

- Tokugawa Ieyasu and Miura Shigenari

- Tokugawa Hidetada and Naruse Masatake

- Tokugawa Hidetada and Nabeshima Tadashige (Nabeshima Naofusa, son of Nabeshima Naoshige)

- Matsudaira Tadayoshi (1580-1607, son of Tokugawa Ieyasu) and Ogasawara Yoshihisa (Ogasawara Kenmotsu)

- Sakabe Gozaemon and Tokugawa Iemitsu

- The childhood friend and retainer, aged 21, was murdered by his 16-year-old beloved as they shared a bathtub, in 1620.[[[21]]] Sakabe was killed by Tokugawa Iemitsu, because he (Sakabe) had embraced and played with other boys in the bath. These boys were pages to Iemitsu.[[[22]]]

- Tokugawa Iemitsu and Hotta Masamori

- Tokugawa Iemitsu and Sakai Shigezumi(1607-1642)

- Abe Shigetsugu (1598-1651, son of Abe Masatsugu) and Tokugawa Iemitsu

- Tokugawa Iemitsu and Uchida Masanobu

- Nakane Masamori (1588-1666) and Tokugawa Iemitsu

- Tokugawa Iemitsu and Kaji Sadayoshi

- Tokugawa Iemitsu and Asakura Toyoaki

- Tokugawa Iemitsu and Takashima Sakon

- Matsudaira Nobutsuna and Tokugawa Iemitsu

- Date Masamune and Tadano Sakujurō (Tadano Katsuyoshi)

- In circa 1617 the 50 year-old Daimyō sealed a written vow of love (still in existence) with his favorite boy (koshō,小姓) Tadano Sakujuro, like Takeda Shingen.[[[23]]]

- Maeda Toshitsune and Horio Tadaharu

- Gamō Tadasato(1602-1627, grandson of Gamō Ujisato) and Morikawa Wakasa(extremely handsome page)

- Ishikawa Jōzan( or Ishikawa Shigeyuki, 1583-1672) and Ishikawa Magojūrō

- Jōzan passed away in his beloved Magojūrō's arms, like Pindar(Pindaros).

- Miyamoto Musashi and Miyamoto Iori (Miyamoto Sadatsugu)

- Miyamoto Musashi and Miyamoto Mikinosuke (Miyamoto Sadahide)

- Miyamoto Musashi had never married and adopted beautiful boys (Mikinosuke and Iori) as his sons, just as Uesugi Kenshin did.

- Honda Tadatoki and Miyamoto Mikinosuke (Miyamoto Sadahide)

- Honda Tadatoki loved Mikinosuke extraordinarily, so his wife Senhime was burning with jealousy. Because of her furious jealousy, Mikinosuke was unfortunally expelled.

- Matsudaira Yoshitoshi(daimyō of Himeji) and Morita Zusho

- Kuroda Tadayuki (son of Kuroda Nagamasa) and Kurahachi Masatoshi

- Nabeshima Mitsushige and Yamamoto Tsunetomo[[[24]]]

- Yamamoto was one of koshō (小姓) pages to Mitsushige.

- Tokugawa Tsunayoshi and Yanagisawa Yoshiyasu

- Yoshiyasu served the shogun, 12 years his senior, from ca. 1660 at an early age, and both played major roles in the incident of the 47 ronin of 1701.

- Tokugawa Tsunayoshi loved boys profoundly just like his father Tokugawa Iemitsu. Tsunayoshi had the special harem of which all the members were beautiful boys, and maintained sexual relationships with more than 150 handsome youths. Yanagisawa Yoshiyasu(one of Tsunayoshi's ex-lovers) kept many beautiful boys in his premises and every time shogun Tsunayoshi visited his(Yoshiyasu's) mansion, he presented them to the shogun like Madame de Pompadour's Parc-aux-cerfs.[[[25]]]

- Moriwaki Gonkuro and Mashida Toyonoshin

- On being challenged to a duel in 1667 by a man whose advances he had rejected, sixteen year old Toyonoshin appeals to his thirty one year old lover, with whom he has been in relationship for three years, for assistance. The two end up fighting and defeating the interloper and his henchmen, then prepare for seppuku to atone for having killed the lord's men, only to be forgiven by the lord for their valor.[[[26]]]

- Asano Naganori and Kataoka Takafusa(1667-1703)

- Asano Naganori and Isogai Masahisa (1679-1703)

- Asano Naganori and Tanaka Sadajirō

- Asano Naganori, like other daimyōs, loved many handsome boys very much. And the cause of the Forty-seven Ronin incident was a trouble associated with shudō. When Kira Yoshinaka wanted Asano's beautiful youth Hibiya Ukon, Asano rejected flatly. Indignant Kira, accordingly began to bother Asano one after another.[[[27]]]

- Kira Yoshinaka(吉良上野介義央) and Shimizu Ichigaku (1678 - 1703)

- Ōishi Yoshio(大石内蔵助良雄) and Segawa Takenojō.

- Ōishi Yoshio, the top hero of Chūshingura, played with kabuki actors and kagema in Kyōto. Takenojō, kagema actor, was one of them.

- Aiyama Kōnosuke (1686-?) and Ōishi Chikara (大石主税良金,1688 - 1703).

- Ōishi Chikara, son of Ōishi Yoshio and youngest member of Forty-seven Ronin, suggested by his father to go and play with prostitute in 1702, without hesitation rushed to brothel in Kyōto and bought a male-prostitute named Aiyama Kōnosuke. Chikara and Kōnosuke did swear eternal love. In 1703 as soon as Chikara killed himself by seppuku, Kōnosuke became a buddhist monk and prayed for the repose of Chikara's soul.

- Matsuo Bashō and Tsuboi Tokoku(a.k.a. Mangikumaru (circa 1657~1690)

- Maeda Yoshinori and Ōtsuki Tomomoto (1703-1748)

- Tokugawa Ienobu and Manabe Akifusa

- Hiraga Gennai and Yoshizawa Kuniishi

- Tokugawa Ieshige and Tanuma Okitsugu

- Tokugawa Ieharu and Mizuno Tadatomo (1731-1802)

- Tokugawa Ienari and Mizuno Tadaakira (1763-1834)

Meiji period

- Saigō Takamori and Murata Shinpachi

- Murata, who lived from 1836 to 1877, was reputed to be very beautiful in his youth.

- Ōkubo Toshimichi and Murata Shinpachi

- Both Saigō and Ōkubo fell in love and competed with each other for the boy's hand. Hence these two heroes became rivals and conflicted throughout their lives, as Themistocles and Aristides did.[[[citation needed]]]

References

- ↑ However, it is recorded that Emperor Tenji and Fujiwara no Kamatari were in this relation in Oyamada Tomokiyo, " Nanshoku-kō ", 『男色考』However, it is recorded that Emperor Tenji and Fujiwara no Kamatari were in this relation in Oyamada Tomokiyo, " Nanshoku-kō ", 『男色考』

- ↑ "古事談" ("Kojidan")

- ↑ "台記" or "The Diary of Fujiwara no Yorinaga , "続古事談", "Zoku-Kojidan"

- ↑ "台記" or "The Diary of Fujiwara no Yorinaga"

- ↑ However, it is recorded that Emperor Tenji and Fujiwara no Kamatari were in this relation in Oyamada Tomokiyo, " Nanshoku-kō ", 『男色考』

- ↑ "古事談" ("Kojidan")

- ↑ "台記" or "The Diary of Fujiwara no Yorinaga , "続古事談", "Zoku-Kojidan"

- ↑ "台記" or "The Diary of Fujiwara no Yorinaga"

- ↑ "吾妻鏡","Azuma Kagami)"

- ↑ "本朝浜千鳥", Honcho Hamachidori

- ↑ ("塩尻", Shiojiri, "太平記", Taiheiki, "麓の色", Fumoto no iro

- ↑ "応仁前記"",Onin zenki"

- ↑ 新井白石 Arai Hakuseki " 藩翰譜" "Hankan-fu"

- ↑ "大内義隆軍記","Ōuchi Yoshitaka Gunki"

- ↑ Leupp, pp.53-54

- ↑ "Shōnen-ai no Renga Haikai shi" 1997, ISBN 4-8060-4623-x

- ↑ 新井白石 Arai Hakuseki " 藩翰譜" "Hankan-fu" ,太田錦城 Ota Kinjo " 梧窓漫筆" ,"Goso-manpitsu"

- ↑ "戦国美少年四天王"

- ↑ "亜相公御夜話" or "Night-stories of Maeda Toshiie"

- ↑ 太田錦城 Ota Kinjo " 梧窓漫筆" ,"Goso-manpitsu"

- ↑ 太田錦城 Ota Kinjo " 梧窓漫筆" ,"Goso-manpitsu"

- ↑ 太田錦城 Ota Kinjo " 梧窓漫筆" ,"Goso-manpitsu"

- ↑ 『片倉代々記』,"Katakura Daidaiki"

- ↑ Louis Crompton, p.439

- ↑ Crompton, p.439

- ↑ "寛明記事" ("Kanmei-kiji") or "The Chronicle from kan'ei to meireki"

- ↑ "Date Masamune's letters", Tokyo: Sinchosensho,1995, ISBN 4106004798 ISBN 978-4106004797

- ↑ "葉隠","Hagakure"

- ↑ "三王外記""Sanno gaiki"or "The secret history of the three rulers", 御当代記" or "The history of Tokugawa Tsunayoshi",etc.

- ↑ Rictor Norton, Ed. My Dear Boy: Gay Love Letters through the Centuries; pp.71-72

- ↑ "Seichu bukan","誠忠武鑑","Chugi Bukegirimonogatari","忠義武家義理物語","Chugi Taiheiki-taizen","忠義太平記大全",etc.

Sources

- Ihara Saikaku (Paul Gordon Schalow, trans.). The Great Mirror of Male Love. Stanford University Press, 1990. ISBN 978-0804718950

- Leupp, Gary. Male Colors: The Construction of Homosexuality in Tokugawa Japan. University of California Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0520209008

- Pflugfelder, Gregory. Cartographies of Desire: Male-Male Sexuality in Japanese Discourse, 1600-1950. University of California Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0520251656

- Watanabe, Tsuneo et Jun'ichi Iwata, La voie des éphèbes: histoire et histoires des homosexualités au Japon. Paris, 1987. ISBN 2865090248

- Watanabe, Tsuneo and Jun'ichi Iwata. The Love of the Samurai: A Thousand Years of Japanese Homosexuality. GMP, London, 1989. ISBN 0-85449-115-5

- Miller, Stephen D. (edited), Partings at Dawn : An Anthology of Japanese Gay Literature. 1996. ISBN 0-940567-18-0

- Hanafusa Shiro, Nanshoku-ko, 1928.

- Inagaki Taruho, Inagaki Taruho Taizen 2, 1969.

- Domoto Masaki, Nanshoku Engeki-shi, 1970.

- Domoto Masaki, Nanshoku Engeki-shi, (New rev.), 1976.

- Iwata, Jun'ichi, Honcho Nanshoku-ko, 1974.

- Iwata, Jun'ichi, Nanshoku bunkenshoshi, 1973.

- Minakata Kumagusu, Minakata Kumagusu Zenshu 9, 1973.

- Hasegawa Kozo and Tsukikawa Kazuo (eds.), Minakata Kumagusu nanshoku dangi, 1991. ISBN 4896946138

- Iwata, Jun'ichi, Honcho Nanshoku-ko & Nanshoku bunkenshoshi, 2002. ISBN 4562034890

- Sunaga Asahiko, Bishōnen Nihonshi, 2002. ISBN 4336043981

- Sunaga Asahiko et al.(eds.), Shomotsu no Okoku 8; Bishōnen, 1997. ISBN 4336040087

- Sunaga Asahiko et al.(eds.), Shomotsu no Okoku 9; Ryoseiguyu, 1998. ISBN 4336040095

- Sunaga Asahiko et al.(eds.), Shomotsu no Okoku 10; Doseiai, 1999. ISBN 4336040109

- Hanasaki kazuo, Edo no Kagemajaya, 1980, 1991.

- Hanasaki kazuo, Edo no Kagemajaya, (New rev.), 2002. ISBN 4895222853

- Hanasaki kazuo, Edo no Kagemajaya, (New rev.), 2006. ISBN 4895224708

- Ujiie Mikito, Bushido to Eros 1995. ISBN 406149239x

- Ujiie Mikito, Edo no Seidan, 2003. ISBN 4062683857

- Hiratsuka Yoshinobu, Nihon ni okeru Nanshoku no Kenkyu, 1983.

- Shibayama Hajime, Edo Nanshoku-ko, 3 vol. 1992-1993. ISBN 4826501501, ISBN 4826501528, ISBN 482650151x

- Saneyoshi Tatsuo, Honcho Bishōnen-roku, 1993. ISBN 4875199155

- Kakinuma Eiko, Kurihara Chiyo et al. (eds.), Tanbi-Shosetsu, Gay-Bungaku Book Guide, 1993. ISBN 4893673238

- Shunroan Shujin (Watanabe Shin'ichiro), Edo no Shikido; Nanshoku-hen, 1996. ISBN 4916067177

- Watanabe Shin'ichiro, Edo no Keibo-jutsu, 2005. ISBN 4106035472

- Koishikawa Zenji (edited), Nanshoku no minzokugaku, ISBN 4826503830

- Koishikawa Zenji (edited), Gei no minzokugaku, ISBN 4826504357

- Timon Screech, Takayama Hiroshi(translat.), Shunga, 1998. ISBN 4062581280

Look up pederastic in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

See also

External links

- SOURCE FOR THIS ARTICLE:http://lgbt.wikia.com/wiki/Pederastic_couples_in_Japan