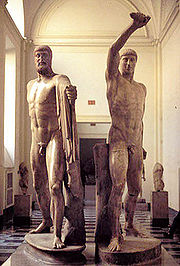

Harmodius and Aristogeiton

| Part of the boylove history series |

|

| Portal:History |

Harmodius and Aristogeiton (died 514 BC) were a pederastic couple from Athens whose assassination of the tyrant Hipparchus was credited with bringing democracy to Athens. Others argued that their act sprang from a desire for personal revenge, and was only later processed by democratic politicians and historians into a patriotic act.

The courage and loyalty shown by the lovers in resisting tyranny was believed to be a specific attribute of pederasty.

The Peisistratid Tyranny

Athens flourished under the tyranny of Peisistratus (561-556, 546-527 BC), and when rule passed to his two sons, Hippias and Hipparchus, the city continued to accept, albeit grudgingly, the now hereditary tyranny.[1]

Hippias, the elder brother, wiser and more statesmanlike, ruled Athens as tyrant. Hipparchus, on the other hand, "was fond of amusement and love-making." [2]

Harmodius and Aristogeiton 514 BC

Thucydides described Harmodius as being "in the flower of his youth, of great beauty".[3] He was the beloved of Aristogeiton, an Athenian of middle rank. Their relationship came under direct threat when Hipparchus, having fallen in love with Harmodius, made continual attempts to seduce the young man.

Harmodius rejected all sexual advances from Hipparchus, something which angered the second-most-powerful man in Athens and caused him to plot revenge.

In the lead up to a sacred procession, Harmodius's sister was enlisted to carry a basket. But she was expelled from the event and publicly humiliated by the implication she was not a virgin and therefore not worthy.

This deliberate humiliation, engineered by Hipparchus, angered Harmodius – but it enraged his lover, Aristogeiton, who plotted revenge.

Aristogeiton and his beloved, along with other co-conspirators, developed a plan to overthrow the Peisistratid tyranny by assassinating both Hippias and Hipparchus.

On the day of the Great Panathenaea, an Athenian festival celebrated every fourth year, Harmodius and Aristogeiton prepared to attack the Peisistratids with daggers. But before they could begin, they saw Hippias engaging in conversation with some of the plot's co-conspirators. Believing their plot foiled, the two lovers rushed to effect what damage they could. They came across Hipparchus and "in all the fury that a man in love and a man humiliated could feel, they stabbed until they killed him."[4]

Harmodius was immediately killed by Hipparchus's guards, while Aristogeiton was taken alive and tortured in an attempt to discover the identity of the co-conspirators. Aristogeiton convinced Hippias he would confess all if the tyrant would only shake his hand as a pledge of good faith. Hippias did so, but was immediately taunted by Aristogeiton for shaking the hand of his brother's murderer. Enraged, Hippias lost control and slew Aristogeiton on the spot.[5][6]

Aftermath

Hippias continued as tyrant for another four years but, in the aftermath of his brother's assassination, he developed a deep mistrust of pederasty and his rule became harsh and paranoid. He allied himself with the Persians who had attacked the institution of pederasty in Ionia in order to bring those cities under dictatorial control.[7]

Unhappiness with the ever-harsher tyranny grew until finally the Spartans were recruited to help drive out the last of the Peisistratids. Hippias fled to Persia where he became a vocal critic of pederasty.[8]

Immortality

Within a year of the defeat of tyranny, a statue celebrating Harmodius and Aristogeiton was erected in the agora. They were the first historical figures to receive such an honour and their fame remained steadfast, often uniting Athenian partisans of vastly different political ideals. The moment the Persians were defeated at Salamis in 480 BC, a new, bigger, bolder statue of the heroic lovers was erected.

Although writers such as Thucydides carefully debunked many of the mythological elements surrounding the Harmodius and Aristogeiton story, at no time was the symbolic importance of this pederastic dynamic duo seriously threatened.

The statue of Harmodius and Aristogeiton celebrated an ideal pederastic relationship. According to C. Sara Monoson, "the statue invites young men and boys to identify with Harmodius and mature men with Aristogeiton and then for both to 'vicariously savor the homoerotic relationship between the two' (Stewart 1997: 73)".[9] Such a relationship is expected, as a matter of course, to channel its pederastic energy into a betterment of its lovers and the society they belong to. The self-confidence, love of freedom, and intellectual creativity that was to bloom in classical-age Athens was thought to have derived from the ideal represented by this heroic couple. Plato and Xenophon, in their later critiques of pederastic relationships that deviated into anal sex (known as "hybris" in Ancient Greece, and seen as dishonorable, abusive, and shameful), never disputed the rightness of ethical pederastic relationships modeled on that of Harmodius and Aristogeiton.[10][11][12][13]

References

- ↑ The Life of Greece, by Will Durant p.123

- ↑ http://data.perseus.org/citations/urn:cts:greekLit:tlg0086.tlg003.perseus-eng1:18

- ↑ http://data.perseus.org/citations/urn:cts:greekLit:tlg0003.tlg001.perseus-eng1:6.54

- ↑ Homosexuality in Greece and Rome, ed. T. Hubbard, p.61

- ↑ http://data.perseus.org/citations/urn:cts:greekLit:tlg0086.tlg003.perseus-eng1:18

- ↑ http://data.perseus.org/citations/urn:cts:greekLit:tlg0003.tlg001.perseus-eng1:6.54

- ↑ Pederasty and Pedagogy in Archaic Greece, by William Armstrong Percy III, p.121

- ↑ Pederasty and Pedagogy in Archaic Greece, by William Armstrong Percy III, p.182

- ↑ The Allure of Harmodius and Aristogeiton p.48, by C. Sara Monoson, in "Greek Love Reconsidered", ed. T. Hubbard, NAMBLA Topics 9

- ↑ Homosexuality in Greece and Rome: a sourcebook of basic documents, Edited by Thomas K. Hubbard, p.15

- ↑ The Allure of Harmodius and Aristogeiton pp.42-51, by C. Sara Monoson, in "Greek Love Reconsidered", ed. T. Hubbard, NAMBLA Topics 9

- ↑ Pederasty and Pedagogy in Archaic Greece, by William Armstrong Percy III, pp.181-2.

- ↑ Greek Homosexuality, by K.J. Dover, pp.41-2.

See also