Greek love

Greek love is a relatively modern English term[nb 1][1] synonymous with other similar phrases. The ambiguity of an ancient Greek model of "friendship" can imply a male bonding between equals or a spiritual, educational and/or sexual union of males of varying age.[2] Quotation marks are generally placed on either or both words, i.e., "Greek" love, Greek "love" or "Greek love".

The term is documented as beginning in German writings between 1750 and 1850 with such terms as "griechische Liebe" (Greek love), "socratische Liebe" (Socratic Love) and "platonische Liebe" (Platonic love), which were designated for male-male attractions.[3]

Apart from its perceived historical connotation, no such term is found in any surviving text from any ancient source. While there are terms, such as Mos Graeciae (Greek custom) and Mos Graecorum (the Greek Way), they were never deployed in reference to pederasty, but for a variety of Greek practices.[1]

| Part of the boylove history series |

|

| Portal:History |

Overview

The term "Greek love" has been used interchangeably with other similar phrases, such as "Platonic love" and "Socratic Love", (derived from Marsilio Ficino's term "amor platonicus" from his translations of the Symposium). The meaning of the individual terms has drifted over time.

Authors and historians will sometimes add the varied names together between brackets to be clear the reader knows their written intentions. Richard A. Posner, (author and judge, United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit in Chicago) author of "Sex and Reason" dissects the subject, and illustrates the use of bracketing his own coined term, discussing men who prefer sex with other men, over women, and men who preferred sex with women, but were quick to substitute a man or (preferably) a boy when women were not available;

"The first group dominates the homosexual subculture of today; the last group dominated "Greek Love" (which should really be called Athenian Love because we know little about the sexual customs of the other city states). Provided we are aware of this difference, we shall not get into trouble if we call Greek love homosexual."[4]

The three terms are associated with educational, civic and philosophical ideals as well as the sexual implications.[5] Relationships often transcended the physical or the erotic, the adult being invested with responsibility for the moral and spiritual welfare of the boy: abuse, exploitation and actual sexual penetration of the younger partner was not acceptable as the youth was expected to mature into a respected and honored Greek citizen. Such was the attitude of the time that submitting to the act would be distasteful and dishonorable, while such fate did not necessarily befall the abuser.[6]

Several revivals throughout documented history attempted to bring back ancient Roman and Greek philosophies as well as other classic traditions. Interests in history, archeology, art, literature, astronomy, medicine and social sciences of the ancient Greeks survive today due in great part to these revivals of interest, beginning with the Carolingian Renaissance, Renaissance of the 12th century, the Renaissance of the 14th–17th centuries. During these times interest in the teachings and philosophies of Socrates, Plato and Xenophon emerged again.

Linguistic history

The term "Greek love" has come to signify the original English use of "Platonic love", that of a male-male sexual attraction made respectable by refering to antiquity. Greece became a reference point by homosexual men of a specific class and education.[7] The first use of that phrase dates back to 1636 with "Platonic Lovers" by Sir William Davenant.[8] The latter phrase was derived from the writings of Marsilio Ficino who coined the terms amor Socraticus. There is no linguistic link to the Greek language.

In a German university of the late 18th century, a journal began circulating with the writings and letters of students. The journal centered around the philosophies of Plato and Socrates. In one journal a letter is published from a student proclaiming his attraction to other men. Citing both phrases in German ("socratische Liebe" - Socratic Love, "platonische Liebe" - Platonic love), the author of the letter also coins the phrase "griechische Liebe" (Greek love).

Greek love was sometimes idealized and sentimentalized. Such a reading of the ancient Greeks can imply the beginning of sexual liberation, especially for 19th century homosexuals.[9]

Historical background

Man presents a leg of mutton to a youth with a hoop, in an allusion to pederasty.[10] Athenian red-figure vase, ca. 460 BCE

The history of the concept, predates the term by nearly 3000 years. Institutional Greek homosexuality as well as Greek pederasty (the erotic relationship of an adult male erastes with a young adolescent eromenos), appeared on the Greek mainland, as early as the 7th century B.C. Both Sparta and Athens established similar cultural and social phenomenon.

Homosexual activity in ancient civilizations is common. Many civilizations offer few sexual options in a rigid class system. Greek men stayed within their own class, if not within their own gender. Marriage was expected but offered little more than relations to produce offspring, as the two genders were separated in public and traditionally did not even take meals together. Women were secluded in Ancient Greece. The natural step was to turn to who was available and accepting.[11] Ancient sexuality was not approached as a gender specific attraction. Homosexuality, is also a modern term. It has only been in use for just 130 years.[12] The concept of strict sexual separation of the genders is also a relatively new idea. Not until strict church doctrine taught this ideology did it become a moral issue. Up until that time there simply was little to no standard against it.

A true homosexual subculture did not exist in ancient Greece.[13] Homosexuality is an attraction to the same anatomical sex.[14] While there were individuals of both sexes that were only attracted to their own gender they would have no reason not to marry for the same benefits afforded every adult of Greece. The marriage was not to become something else or to hide the males attractions, but because that is what men did at a specific time in their lives. They would have no reason to hide their desires or their affairs as the ancient society saw it as natural and even honorable.

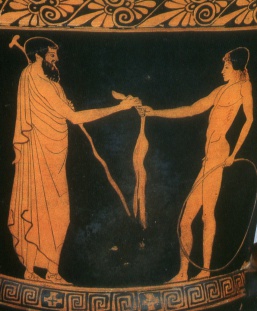

It appears to have been a great honor to be "mock" abducted in a nearly theatrical way, and spirited off to the residence of the Erastus by his friends where the Eromenos is treated with food, wine and seduction while held "captive". The stylised faux "kidnapping" may last for several days as gifts and song are bestowed on the youth, who is returned safely home. It is clear that the goal is the acceptance from the youth, who may turn away the advances. Generally the young man or adolescent boy will be sought after by many who, become attracted by the physical perfection of the athlete during competition in the Greek games. There is overwhelming evidence to illustrate the social phenomenon. Literary work such as the Socratic dialogues of Plato, for example, hundreds of Greek vases displaying a range of emotive and expressive guises, and the words of the actual love struck Greek's themselves carved into the many stadium tunnels, where the athletes would wait for their events as well as on the wall's columns and even natural rock of the country. Most of the Ancient Greek love poems are attributed to the traditions of Kalos.

Male same-sex relationships of the kind portrayed by the "Greek love" ideal were increasingly disallowed within the Judaeo-Christian traditions of Western society, though there was more tolerance within Asian cultures until recent times.[15] The earliest reference to the modern ideology is from that of Marsilio Ficino after the fall of the Byzantine Empire. In his comments of Plato's work in 1469, Ficino describes "amor socraticus", however it must be said that Ficino, influenced by the church doctrine attempted to water down its meaning and concept and concluded that the male love was allegorical.[16] In his commentary to the Symposium, Ficino carefully separates the act of sodomy, which he condemned, and lauded Socratic love as the highest form of friendship. He believed that men could use each other's beauty and friendship to discover the greatest good, that is, God. Ficino christianised the theory of love presented by Socrates.[17]

Romanticism

Romantic Hellenism

As far back as the Roman Republic and Empire, Greek literature assumed a central place in classical education. The classics of Greek poetry, theatre and mythology permeated the civilizations that followed in great revivals of the arts and sciences. This was particularly characteristic of Renaissance Italy in the 14th century. The writings of the Roman Empire, which both preserved their own traditions and those of ancient Greece were rediscovered at the end of the Byzantine Empire. 400 years later, influential figures such as Byron, Shelley, Goethe and Winckelmann of early 18th century Britain and Germany, paid homage to the perceived sexuality of Greek life and culture.

German scholar and writer, Johann Joachim Winckelmann, did more than any other intellectual or artistic figure in the 18th century to promote the Greek ideal of beauty.

Byron and his school-mates at Harrow would have read the classics. They would have had an understanding of the term, "Greek love".[18][19]

Ours too the glance none saw beside;

The smile none else might understand;

The whisper'd thought of hearts allied,

The pressure of the thrilling hand.

from:To Thyrza, October 11, 1811

The poet, Shelley, a pupil at Eton, immersed himself in Greek literature, his Platonic studies leading to a translation of the Symposium (1818) and in the same year a ‘Discourse on the Manners of the Antient [sic] Greeks Relative to the Subject of Love’ which stands as the first published essay (after Bentham’s unpublished writings of 1785) on the subject of homosexuality. The significance of this document lies in its repudiation of the evasions of contemporary scholarship which had blurred the perceptions of Greek love as a sexual practice. Shelley, however, was restrained by the times, so that much of the essay is questionable, while drawing a line between ‘ridiculous and disgusting conceptions’[20] and an oblique reference to ‘natural’ orgasmic release:

"If we consider the facility with which certain phenomena connected with sleep, at the age of puberty, associate themselves with those images which are the objects of our waking desires…it will not be difficult to conceive the almost involuntary consequences of a state of abandonment in the society of a person of surpassing attractions, when the sexual connection cannot exist, to be such as to preclude the necessity of so operose and diabolical a machination as that usually described".

The ‘Discourse’ was intended as an introduction to his translation of ‘The Symposium’, but both documents were too daring for the time, and publication of translation (as ‘The Banquet’) and essay had to wait almost a century. In spite of its limitations, the document has nevertheless been considered as ‘a pioneering work in a field not fully and freely explored by an English scholar until Kenneth Dover’s authoritative study of 1980’. (Crompton)[21]

Victorian Hellenism

The ‘Uranians’, as they were called, at a time when Victorian justice upheld the illegality of all male sexual relations, embraced a number of distinguished men of letters, including William Johnson Cory, Gerald Manley Hopkins, Walter Pater, Oscar Wilde and the above-mentioned John Addington Symonds who defines the term:

I shall use the terms Greek Love, understanding thereby a passionate and enthusiastic attachment subsisting between man and youth, recognised by society and protected by opinion, which, though it was not free from sensuality, did not degenerate into mere licentiousness.[22]

While this group of neo-Hellenists was finding support and inspiration from an ancient culture, the voices of Karl-Heinrich Ulrichs, Karl-Maria Kertbeny and Richard von Krafft-Ebing were being heard across Europe, articulating their theories of ‘homosexuality’ (coined by Kertbeny), sexual orientation and gender inversion which were to make an increasing impact in legal, medical and sociological circles. The Uranians, almost all classically-educated Oxonians, stood aside from such scientific controversies, with their spiritual, philosophical and emotional antecedents. Their Hellenic appellation derives from both Plato’s ‘heavenly’ love and the birth of Aphrodite as described in Hesiod (Theogony), not to be confused with ‘Urning’, a term coined by Ulrichs to denote ‘a female psyche in a male body’ ('Urning' also derives from Classical sources, particularly the Symposium).

The immediate Hellenist precursors of the Uranians were the influential literary and reformist figures of Matthew Arnold, John Stuart Mill, and Benjamin Jowett.

Michael Kaylor identifies “two forms of erotic positioning in relation to this ‘boy-worship’— as well as the fulfilment and outcome of such an erotic attachment — one ‘conciliatory to social orthodoxies’, the other ‘pervasively dissident’.

Walter Pater seems to have actualised his paederastic desires only once, threatening his academic position so thoroughly that he sublimated thereafter, a choice that later matured into an appreciation for such sublimation; Oscar Wilde actualised most of his paederastic desires, a ‘madness for pleasure’ that ruined many lives, and not just his own.”

Influence in art

The Romans were inspired enough by Greek art to copy many of their great works. The subject of Eros, and the traditions of male contact were repeated in many of the Roman sculptures described by Johann Winckelmann in a three volume set of books.[23]

During the Renaissance, artists such as Leonardo Davinci and Michelangelo discovered Plato and used his philosophy as artistic muse for inspiration for their greatest works. The new paganism, liberated their senses and mind. Greek love was an ideal love in its essence, after the platonic pattern.[24] Michelangelo presented himself to the public as a Platonic lover of men in 16th century Italy. His art combined and alternated between catholic orthodoxy and pagan enthusiasm in many of his works. The sculpted likeness of a local saint, Proculus and his first great masterpiece, Bacchus illustrate this. Michelangelo's next two pieces, Pieta and The David, pay respect to his faith and Eros.[25] In later revivals these works were drawn on as further inspiration. The 18th century artists of the time of Wincklemen, would, at times produce art, representing ancient society and Greek love in their Neoclassical work.[26] Artist, Jaques-Louis David's "Death of Socrates", is meant to be a Greek painting, imbued with an appreciation of "Greek love". Socrates is a tribute and documentation of leisured, disinterested, masculine fellowship.[27]

Academic and scholarly contradictions and controversy

In his paper, Reconsiderations about Greek Homosexualities (2005), Percy takes Dover to task in connection with what he terms ‘the sexual-role dichotomization’. He refers here to the depiction of the erastes/eronemos relationship as defined by sexual roles, active and passive respectively. This dichotomy was connected by Dover to other sexual and social mores which conferred a certain propriety on the role of the male adult Athenian as an active penetrator while denigrating the passive/penetrated role. As a result, ‘penetration’ has become a focal point in the scholarship to the extent that the concept of domination takes precedence over any other aspects of Greek sexuality. The ‘constructionists’, Foucault and Halperin, and their many followers, have extended this analysis, but the ‘Dover dogma’ remains at the heart of the discussion.

Percy underlines the complexity of the Greek male experience which is not served by reducing same-sex behaviors to the purely physical or sexual. He places at the forefront of his discussion the established pederastic system of education which ‘became a way to lead a boy into manhood and full participation in the polis’ which in turn was able ‘to benefit the city in a wide range of potential ways.’ The training and indeed inspiration provided in the pederastic relationship ‘released creative forces that led to what has been called the Greek "miracle".’ He argues that the coexistence of ‘lustful pederasty’ and pedagogical pederasty represented ‘two ways that the Greeks understood the desire and relationship involved in boy-love’, and its vital educational force.

Percy strongly criticizes Dover’s ‘myopic view of the institution of pederasty' and ‘lack of understanding of homosexuality verging on homophobia, a crucial point being Dover’s way of dealing with the sexual terminology: retaining the word ‘sexual’ for hetero relations while being inclined to treat homosexuality ‘as a subdivision of the quasi-sexual or pseudo-sexual (not para-sexual)’.[Dover, 1978, Preface] He does not, however, neglect to mention the availability of flute girls, slaves, prostitutes, and hetairai to dispel any notion that the elite Greeks had no opportunity for heterosexual contact before marriage (typically delayed until the age of 30), concluding (in a footnote) that the incidence of homosexual choice would still most likely have been higher than in today's world (as measured by Kinsey). No exclusive homosexuals are recorded in the epics or myths, though the stories - as with Achilles and Patroclus - continued to be homosexualized even as late as the Roman period.

Academic sources

Dr James Davidson, M.A. (Oxford), M.A., M.Phil. (Columbia) D.Phil. (Oxford)[28]

Kenneth Dover|Sir Kenneth James Dover, FRSE, FBA, former President of Corpus Christi College, Oxford (born March 11, 1920).[29]

'Dr. Louis Crompton, Professor of English, University of Nebraska[30]

Professor Thomas K. Hubbard, Greek and Roman Literature, Literary Theory, University of Texas at Austin [31]

Notes

- ↑ The word "Modern" is defined as relative to ancient history. Not to be confused with "Contemporary", which means "in use today".

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Williams, Craig Arthur (June 10, 1999). Roman homosexuality. Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 72. ISBN 9780195113006.

- ↑ Taddeo, Julie Anne (July 18, 2002). Lytton Strachey and the search for modern sexual identity. Routledge; 1 edition. pp. 21. ISBN 978-1560233596.

- ↑ Gustafson, Susan E. (June 2002). Men desiring men. Wayne State University Press. pp. [1]. ISBN 978-0814330296.

- ↑ Posner, Richard (January 1, 1992). Sex and reason. Harvard University Press. pp. 30. ISBN 978-0674802803.

- ↑ Kuzniar, Alice A. (July 1, 1996). Outing Goethe & his age. Stanford University Press. pp. 7. ISBN 978-0804726153.

- ↑ Simon, Rita James (May 25, 2001). A comparative perspective on major social problems. Lexington Books. pp. 4-5. ISBN 978-0739102480.

- ↑ Petrilli, Susan (November 14, 2003). Translation, translation. Rodopi. pp. 623. ISBN 978-9042009479.

- ↑ The Encyclopaedia Britannica (1911). The Encyclopaedia Britannica Eleventh edition. Encyclopaedia Britannica. pp. 825. ISBN 978-1593392925.

- ↑ Haggerty, George E. (June 15, 1999). Men in love. Columbia University Press. pp. 141. ISBN 978-0231110433.

- ↑ Antike Welten: Meisterwerke griechischer Malerei as dem Kunsthistorischen Museum Wien, 1997, pp.110-111

- ↑ Posner, Richard A. (January 1, 1992). Sex and reason. Harvard University Press. pp. 146-149. ISBN 978-0674802803.

- ↑ Tamagne, Florence (August 2004). History Of Homosexuality In Europe, 1919-1939. Algora Publishing. pp. 6. ISBN 978-0875863566.

- ↑ Rushing, William A. (June 27, 1995). The AIDS epidemic. Westview Press. pp. 19-20. ISBN 978-0813320458.

- ↑ D'Augelli, Patterson, Anthony R., Charlotte (May 3, 2001). Lesbian, gay, and bisexual identities and youth. Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 27. ISBN 978-0195119534.

- ↑ Crompton, Louis: Homosexuality and Civilization, First Harvard University Press paperback edition, 2006 pp.([213], 411 & passim)ISBN 978-0674022331

- ↑ Fone, Byrne R. S. (May 15, 1998). The Columbia anthology of gay literature. Columbia University Press. pp. 131. ISBN 978-0231096706.

- ↑ Aldrich, Robert (November 15, 1993). The seduction of the Mediterranean. Routledge; 1 edition. pp. 38. ISBN 978-0415093125.

- ↑ Crompton, Louis:Byron and Greek Love - Homophobia in 19th century England. GMP Publishers Ltd 1998/The Cromwell Press. Introduction p.11

- ↑ MacCarthy, Fiona: Byron, Life and Legend. John Murray, London 2002. p.39

- ↑ Crompton (in Byron & Greek Love p.294-5, refer Note 4)

- ↑ Crompton, Louis: Byron and Greek Love: Homophobia in 19th-Century England. London: Faber and Faber, 1985

- ↑ Symonds, J. A.: A Problem in Greek Ethics: London: Privately printed, ISBN 978-1605063898

- ↑ Verstraete, Provencal, Beert C., Vernon (February 13, 2006). Same-Sex Desire and Love in Greco-Roman Antiquity and in the Classical Tradition of the West. Routledge; 1 edition. pp. 15. ISBN 978-1560236047.

- ↑ Taylor, Rachel Annand (March 15, 2007). Leonardo the Florentine - A Study in Personality. Kiefer Press. pp. 483. ISBN 978-1406729276.

- ↑ Crompton, Louis (October 31, 2006). Homosexuality and civilization. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. pp. 270. ISBN 978-0674022331.

- ↑ Aldrich, Robert (November 15, 1993). The seduction of the Mediterranean. Routledge; 1 edition. pp. 136. ISBN 978-0415093125.

- ↑ Crow, Thomas E. (June 20, 2006). Emulation. Yale University Press; Revised edition. pp. 99. ISBN 978-0300117394.

- ↑ [2]

- ↑ [3]

- ↑ [4]

- ↑ [5]

Bibliography

- Crompton, Louis (1998). Byron and Greek Love. London: GMP. ISBN 9780854492633.

- Crompton, Louis (2003). Homosexuality & Civilization. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674022331.

- Fone, Byrne (1998). The Columbia Anthology of Gay Literature. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231096706.

- Gustafson, Susan (2002). Men Desiring Men. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 9780814330296.

- Haggerty, George (1999). Men in Love. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231110433.

- Kuzniar, Alice (1996). Outing Goethe & His Age. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804726153.

- Maccarthy, Fiona (2004). Byron: Life and Legend. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 9780374529307.

- Posner, Richard (1992). Sex and Reason. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674802803.

- Symonds, John (2007). A Problem in Greek Ethics: Paiderastia. City: Forgotten Books. ISBN 9781605063898.

- Taddeo, Julie Anne (2002). Lytton Strachey and the Search for Modern Sexual Identity: the Last Eminent Victorian. New York: Routledge. ISBN 9781560233596.

- Tamagne, Florence (2004). History of Homosexuality in Europe, 1919-1939. New York: Algora Publishing. ISBN 9780875863566.

- Williams, Craig (1999). Roman Homosexuality. Oxford Oxfordshire: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195113006.