A review of You Can Be A King If You Are Brave by Peter Thomas Wolfe

|

News

WARNING: This review contains spoilers. from Greek Love Through the Ages

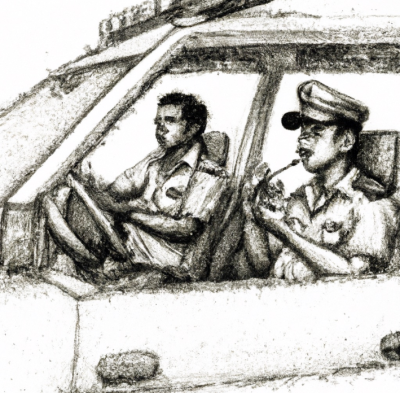

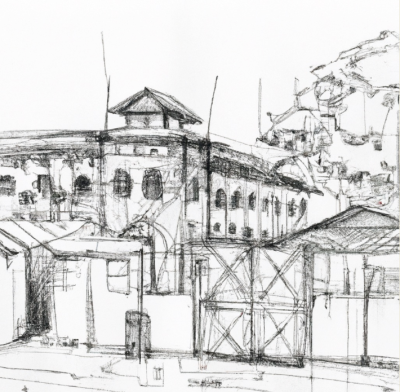

In one very important respect, however, it is not two stories. “The Child is Father of the Man.” The child sex abuse industry which finally destroys Adam would assuredly be quick to assert that he was proof of how the “abused” almost inevitably go on to become “abusers”, thus underlining how important it is that their preventative work is well-funded through fat salaries. Even gay activists, normally furious at any suggestion that their sexuality might not be entirely innate (since the notion they might have some choice threatens the idea they cannot be blamed for it), apparently dare not challenge this dogma. However, the connection Adam feels between his falling in love with a boy and his much earlier experience of having been loved as one very much challenges it. The boy Adam was over the moon about consummating his love for his charismatic teacher, Geoff. Thereafter, he was indeed traumatised, but by the horrific ending of the affair, rather than the affair itself. The subsequent development of his sexuality is subtly convincing. He has a long but chaste engagement to a young woman he believes at first he loves, but breaks it off once he realises his feelings lack depth, while discovering just afterwards a strong emotional pull towards such boys as he, at first inadvertently, meets in Rangoon. Soon, “he understood himself more clearly and accepted that he was a man who, like the teacher he had so loved when he was a teenager, felt a physical, social, emotional, and sexual attraction to adolescent boys.” Immediately after he had succumbed to Chit Ko’s determination that they fully consummate their affair, “unexpectedly, tears came to his eye as he recalled those moments with Geoff so long ago when they had made love on Geoff’s bed shortly before he had been killed. They were tears of relief, Adam realised, as the trauma of losing Geoff […] evanesced like a heavy fog vaporised by the morning sun.” Thus it is only the child sex abuse industry’s Newspeak use of the words “abused and “abuse” instead of “loved” and “lover” that is dishonest. Once truthful words are restored, the principle of being one sometimes tending to lead to becoming the other makes good sense. We all surely aspire to relive happy experiences rather than unhappy ones? We are all also fetishists to some extent, and adolescence is a peculiarly influential time, so it is far from surprising that Adam’s unusually happy experience as a pubescent almost inevitably created a desperate urge to recreate it as best as he could in later life.  While the whole story is convincing enough to sound autobiographical, I doubt the second half set in Burma could have been written by anyone not deeply familiar with the country, and indeed the author’s Amazon page reveals he lived there at the same time as his protagonist and worked in a similar field. In this respect, it reminds me of Gary Shellhart’s Kite Music, another excellent novel with boy-love as a central theme, but set in neighbouring Thailand in 1967. Shellhart (whose protagonist was an American Peace Corps volunteer, so little different) showed a similar deep familiarity with his setting and a love and understanding of the local culture. Oddly though, considering the explosion of mass tourism and other forms of globalisation since Kite Music was published in 1988, because Burma has been partially isolated from the rest of the world by its military dictatorship for two-thirds of the last sixty years, it remains less known to outsiders today than Thailand already was then. You Can Be a King if You are Brave is thus not only fascinating for its lively portrayal of life in Rangoon, but priceless for what it reveals about the practise of Greek love there. I am fairly sure the only previously published writing on this in English was the “Rangoon” chapter of Michael Davidson’s autobiographical Some Boys (1969), set in 1948, but that only told of the author’s moving love affair with one boy (apparently, and probably wilfully, ignored by those who saw the signs of it), and revealed nothing directly about Burmese attitudes. These attitudes are explored in two ways. First, we are given a portrayal of the small and new foreigner/local boy scene through the eyes of Chit Ko, who had had one experience of it. “Though no one had told Adam, many of the boys had foreigners who would give them clothes and money and take them on trips.” Secondly, we are offered deeper insight through the character Kyaw Win, Adam’s Burmese lawyer, who has apparently never heard of pederasty and is initially shocked, but wise and open-minded, sets out to inform himself and comes to the reasoned conclusion that Burmese society has long given space to warm friendships between men and adolescent boys, with an unspoken tacit acceptance that they might sometimes also be secretly sexual (echoing Davidson’s experience). The novel is particularly interesting when it touches on the difference between Australian and Burmese attitudes towards the scenario Adam presents. All the Australians are in full thrall to the hysteria about child sex that had arisen in the anglosphere some twenty years earlier. They are not of course blind to their own self-interest in terms of careers and funds, as they do all at least acknowledge. Nevertheless they are absolutely self-righteous about what they do. Do-gooder William, founder of an NGO working with children and the man who initiates Adam’s destruction, reacts with genuine incomprehension to his Burmese secretary’s comment on his enthusiasm for massive funding of the campaign against sex with children: “It sounds like a lot of money and resources are being put into this, Saya William. I am sure it is worthwhile, but wouldn’t the money be better spent on getting kids into school or a centre like this?” When Kyaw Win, appointed by the Australian embassy itself to look into Adam’s case reports Chit Ko’s testimony that he was Adam’s enthusiastically willing lover, the Australian policeman who has taken charge refuses to consider it possible, apparently angry that Kyaw Win is not bigoted enough to see what is a self-evident truth to him.  The Burmese involved share the self-interest of the Australians. As William’s secretary says of the police: “They are not interested in the truth, only in pleasing their superiors and getting paid.” The colonel in charge is easily persuaded to agree to a trial in Australia instead of Burma when it is pointed out that this will involve a holiday in luxury accommodation there for himself. Brenda, the woman in charge of SCAAT (fairly obviously the real ECPAT), the international organisation set up to combat sex with children in the anglosphere’s long tradition of arrogant imperialism, explains that the police “realise some significant funding is available for them if they join our regional anti-sex tourism alliance. Nabbing this guy will be a big coup for them.” Nevertheless, it is pretty clear that nobody in Burma “gets” the anglosphere’s hysteria on the subject. By this I don’t mean just mean the boys who want foreign lovers or Chit Ko’s mother, who arranges for him to have one, but the very people in charge of enforcing the brutal repression that the anglosphere had recently bullied and bribed Third World countries into apeing. As Brenda puts it, “‘My experience of people in Myanmar is that they don’t fully understand the enormity of the problem.” I would guess this is broadly true of the world apart from the anglosphere and its European sycophants, and the consequence is that the new, obviously-foreign laws have been treated cynically as nothing more than a useful vehicle for career advancement, blackmail and such like. It is certainly mirrored by the only other book I know of about a foreigner getting into trouble over boys in a poor country, J. Darling’s memoir It’s Okay to Say Yes, in which the same Brazilian police who have thrown him in prison, take him off once a week for a rendez-vous with the very boy he is charged with having sex with, in return for generous tips. Even though they don’t seriously believe in what they are doing, much the most shocking part of the story is nevertheless the behaviour of the Burmese police, who, in order to extract information quickly, start very badly beating up the two boys they are supposed to be protecting the moment they are out of sight of do-gooder William (who had called them). For a moment, I thought their viciousness and cruelty was over-the-top, but then it is pointed out that, “after all, they spent most of their time chasing down and beating up people as directed by their superiors.” And then one remembers that even by the standards of the worst military dictatorships that have existed elsewhere in South-East Asia, the Burmese one has stood out for sheer nastiness and brutality to its own gentle people.  As a foreign aid worker, Adam has unsurprisingly brushed in amicable fashion with some of his compatriots laying the foundations of the local child sex abuse industry before becoming their prey, and one can only imagine his similarly-occupied creator brushed similarly with the real people involved, especially since his portrayal of them sounds so convincing. There is a certain nice irony in imagining how some of such people’s social circle may be outwardly acquiescent in apparent respectful absorption of what they say, whilst remaining secretly impervious to their deceitful propaganda. Such thoughts are, however, very little comfort against the background of the total triumph of ignorance and injustice over love and goodness in this deeply-moving but harrowing story. Nor is it easy to lay aside the gloom one feels on reaching its conclusion, when one remembers how close to reality it is: true stories like this continue to crop up around the world, as poisonously misrepresented as Adam’s by the press and by vested interests, and there is not the slightest sign of abatement.

|